Philip Morrice: An Interview

My first e-mail contact with Philip Morrice took place more than 5 years ago. I discovered his work first by reading the Schweppes Guide to Scotch, a very good reference book about the companies involved in the whisky business (i.e., it lists and gives the history of distillers, blenders and bottlers, as well as the list of their brands). I purchased later on a copy of his second book, the Whisky Distilleries of Scotland and Ireland, or a book retracing the footsteps of Alfred Barnard 100 years later. A total of 1000 copies of this book were printed, unfortunately, most of them got destroyed during a fire. By coincidence, Morrice’s visit took place shortly after the massive shutdown of Scottish distilleries in 1983 and thus, is, for several distilleries such as Glenury or Banff, the last description we have left of them. In addition to these two landmark books, he wrote also the “Harrods book of whiskies”, an Italian version of the Schweppes Guide, “Guida allo Scotch Whisky" and a Portuguese version of the Distilleries of Scotland and Ireland, (O Grande Libro Teachers do Scotch Whisky).

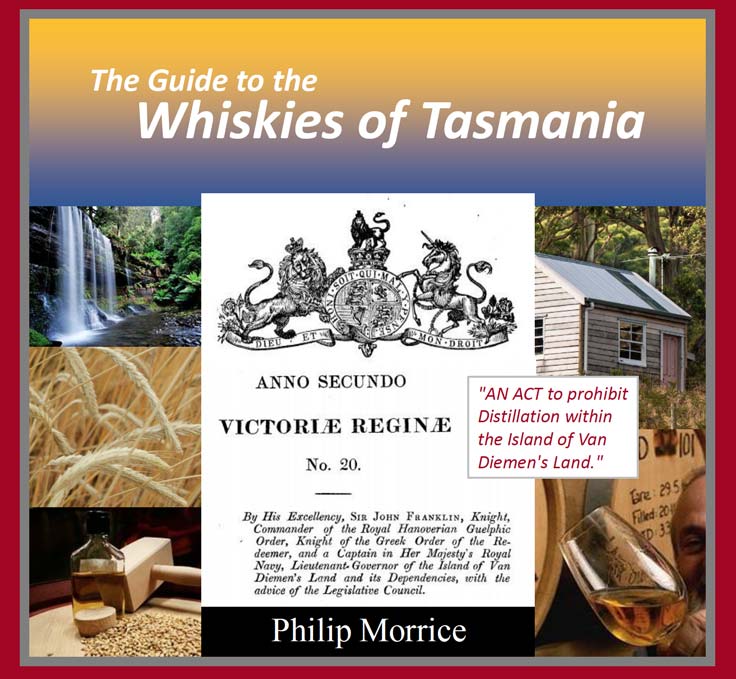

As work in progress, Philip Morrice is now working on a “Guide to the Whiskies of Tasmania”.

As I am very interested in the history of the whisky industry, I could not resist asking Philip Morrice for an interview, which he gladly accepted.

Whisky-news (WN):

Could you please let us know how you became interested in whisky?

Philip Morrice (PM):

I was born and raised in the North-East of Scotland, the home of many malt whisky distilleries, particularly in Speyside. However, in those days whisky distilling was a rather secretive industry, there was no such thing as distillery visits and everyone was tied to his particular brand of blended whisky. In my father’s case, it was “The Famous Grouse”. Whisky and distilling for me was of absolutely no interest and in terms of my future, and developing a career, I soon headed South. That brought me to enter the usual examination process to join HM Diplomatic Service and to embark on a career, which was to take me all over the world – 9 different countries across all five continents.

My first posting was Malaysia and there everyone in those days seemed to drink “Johnnie Walker Red Label”. I recall that it was imported by a very old trading company, Caldbeck Macgregor, which had been founded in Shanghai in 1864. It had grown to become the biggest wine and spirits importer in the Far East. They are still around but I don’t know which Scotch brands they now represent since clearly Diageo (as United Distillers) saw merit in having direct control of their various leading brands and eventually dispensed with their long-standing agency arrangements. However, that was when I first became acquainted with “Hankey Bannister”, which was then owned by Saccone & Speed Limited which seemed to be almost a monopoly supplier of wines and spirits to both the British armed forces (arising from their origins in Gibraltar), and the Diplomatic Service.

My next posting was Venezuela and there was a very strong market there for Scotch, no doubt reflecting the fact that Scotch had become very fashionable to the north and anything that was in vogue in the US was soon making its mark in Caracas. At this time the leading brand was “Buchanan’s”, although another DCL de luxe brand, “Chequers”, which has since disappeared, was being prominently advertised on television. The Venezuelans, however, drank their expensive whiskies with Coca Cola and ice. I knew that this was wrong but how could I educate them if I knew so little about the subject myself! Coincidentally, it was at this time that I was introduced to my first-ever single malt. A colleague in the Embassy had recently been to Islay and had fallen in love with “Bruichladdich”. He managed to persuade some of us to join him in a minimum order of, I think, 12 cases of the 10 years old. And so an entirely new world was opened up for me. Partly on that account and because so many people, when I told them I was from Scotland, saw whisky as the one aspect of Scotland with which they were all familiar, the inevitable barrage of questions followed, which invariably I could not answer and so I decided to educate myself in the subject.

I duly identified two or three existing books, the best of which was undoubtedly the late David Daiches’ “Scotch Whisky: Its Past and Present”. (The good professor subsequently did me the honour of a half-page review in the “Times Literary Supplement” of my first book “The Schweppes Guide to Scotch” by generously describing it as then being “the best book written on the economics of Scotch whisky”! However, I also drew much pleasure and information from Sir Robert Bruce Lockhart’s work “Scotch: the Whisky of Scotland in Fact and Story”. He too had been a British diplomat, albeit one with a much more colourful story to tell than me, but the professional link gave me some encouragement to get on with my own whisky-related literary endeavors.

WN: About your book, “The Schweppes Guide to Scotch", could you please let the readers know how long the research and writing of this book took you?

PM: I started the research in 1977 and then the writing a couple of years later resulting in the book being published in 1983 and so a total of about six years.

WN: What were the challenges you faced with the preparation of this book? And how open were the companies with providing you with the information you needed?

PM: There was no Internet, no word processing and very little published information about the companies and so I had to do a lot of old-fashioned desk research in places like Companies House, Government libraries etc. I also did a lot of interviews by visiting the companies themselves, most of which were quite open and welcoming. Some companies were rather secretive but I would send them a draft of what I had written saying that it would be published unless I received any comments or corrections and this usually produced the desired results. The DCL (now Diageo) as it then was, at first tried to dissuade me from writing the book and it transpired that they were nervous that I would write about the thalidomide scandal. Once I had assured them that my interest was solely in their Scotch whisky business they became quite helpful. And they were extremely supportive when it came to my second book– the re-writing of the Alfred Barnard classic on whisky distilleries. Indeed, Dr Alan Rutherford, who was then the Head of Research and Development at United Distillers (which DCL had become in 1987, the year of publication) kindly wrote the chapter on distillation and did so anonymously.

WN: For your other book, the Whisky Distilleries of Scotland and Ireland, was is your idea or was the work commanded by Harper’s?

PM: it was entirely my own idea but when I took it to S Straker and Sons, the then publisher of Harpers Wine and Spirit Gazette, which had been the original publishers of the Barnard book, they took to it immediately and were delightful people to deal with.

WN: You mentioned in a video (https://vimeo.com/119942927), that it took you several months to prepare it. What was the most time consuming activity in the preparation of the book: The research? Organizing the distillery visits? The writing?

PM: in practice, I worked on the book for about three years. The most time consuming aspect was the actual visits to the distilleries. Each one had to be researched, visited and then the profile chapter written and cleared back with the distillery owner. Again, there was no Internet but word-processing had arrived and so making corrections et cetera became a lot easier

WN: And how easy or difficult was it to visit these distilleries? And do you plan to make a new update version of the book?

PM: it was relatively easy due to modern communications and transport and each visit was set up well in advance and since every distillery manager had heard of Barnard I was invariably assured of a warm welcome. How Barnard had managed all this one hundred years earlier commands enormous respect. I am just starting work on an update of my 1987 book and hope to start my visit program in October this year.

WN: You moved to Australia in 1995 and you are now preparing a new book, Guide to the Whiskies of Tasmania. Could you please tell us a bit more about it?

PM: by comparison with my earlier books, this will be a relatively slim volume as it will probably cover only 13 distilleries, many of which are very new, but I think it will be of considerable interest to whisky lovers because the Tasmanian product is proving to be both sought-after and resplendent of many of the characteristics which has contributed to the success of Scotch whisky in the world. I will follow the Barnard format of combining a travel log with distillery profiles as I am a passionate believer in the merits of whisky tourism and what that can do for the economy and well-being of remote communities where distilleries are often located. There are, of course, many other whisky distilleries in mainland Australia, but the Tasmanian ones stand out because they are all located together in a unique and readily identifiable environment not dissimilar to the way that the Islay distilleries stand apart from the other Scottish distilleries.

|

| The new book of Philip Morrice mo |

WN: As a general comment, what you perception and appreciation of Tasmanians whiskies compares to Scotch whiskies?

PM: A quick comparison is very hard, particularly because the two industries operate on totally different scales. Also blending is at the heart of the Scottish industry whereas it doesn’t exist – at least not yet – in Tasmania. However, the Tasmanian product by and large follows the Scottish malt whisky distilling process using the traditional copper pot still with excellent results to which the numerous international awards stand witness. However, there are exceptions including the Belgrove range of rye whiskies and the Mackey unpeated triple distilled malt whisky, which follows more the Irish model. These add diversity to the Tasmanian offering. Like Scotland, Tasmania is blessed with cool, clean water but also an abundance of high quality local barley which are important contributory factors in making Tasmanian whisky a worthy companion to the wonderful malt whiskies from Scotland. However, they have nothing like the range of taste and bouquet which come with Scotch single malts. But they do have great depth and though they do not have the long years of maturation which you find with Scottish malts, they enjoy a maturity which belies their comparative youth in the wood.

WN: Between your Whisky Distilleries of Scotland and Ireland and the Guide to the Whiskies of Tasmania, more than 25 years have elapsed. Have you keep your whisky passion alive during this time? And if so, how?

PM: All of this was done in the margins of my career as a British diplomat. Inevitably, the demands of the Service caused my writing to become less prolific, although I kept in close touch with developments in Scotch whisky and later became a keen collector of both rare whiskies and whisky-related antiques and memorabilia. In terms of the industry, I kept very much up to date with the companies and the Scotch Whisky Association (the trade association which so effectively promotes and protects generically the interests of the industry) through my work as a diplomat in representing those interests in countries - including Italy, Nigeria, Brazil, Taiwan and Australia - where they were under threat through discrimination or falsification.

WN: How important is whisky for you?

PM: It is my major interest outside my business and sports related activities and my return to writing about whisky, which is becoming increasingly time-consuming, is a clear indicator of where whisky sits in my overall lifestyle profile.

WN: Since you have been a whisky author for over 30 years, what have been the major changes that you noticed from the whisky industry (and companies) regarding the attitude towards whisky authors (e.g., access to information, willingness to share information, support for your research)?

PM: Regarding my current project, I have found the whisky distillers in Tasmania remarkably open, supportive and keen to be involved in the book and its promotion. I hope I shall find the same when I set out with the rewriting of my two earlier books. The Diageo archive is a remarkable source of information and very helpful towards serious authors and researchers. It is probably the most important depository of whisky-related historical material in the world with a professional approach to match.

I believe that the books which I wrote in the 1980’s helped to open the eyes of the industry to the valuable contribution which independent authors can make to the overall benefit of the industry as a whole and to individual companies and their products. Many other excellent authors have followed since and so the literature on whisky is now very extensive and of very high quality and that would only be possible through the co-operation of industry.

WN: Do you have any whisky projects in mind that you would like to share with us?

PM: I have embarked on a task to record as fully and completely as possible the background and current situation as it applies to whisky distilling in Tasmania, adopting the same thorough and punctilious approach I took when writing my earlier books. Accordingly, the current project comprises three components:

i) “The Guide to the Whiskies of Tasmania” (approximately 200 pages to include pen and ink drawings of each distillery plus colour images) in e-book, print and audio;

ii) The historical reprint of “The Schweppes Guide to Scotch” (1983) in e-book and print;

iii) The historical reprint of “The Whisky Distilleries of Scotland and Ireland” (1987) in e-book and print.

This approach is designed to set the Tasmanian book against a background of authority and precedence whilst, at the same time, making a great deal of information of an historical nature about Scotch whisky found uniquely in those two older books available to a wider audience, using the facilities of present-day publishing not available some 30 odd years ago when those books first appeared.

If the project succeeds, this will enable me to fund future whisky-related books to include:

a) a guide to the whiskies of Australia and New Zealand, which will be the Tasmanian guide writ larger;

b) an up-dated version of “The Schweppes Guide to Scotch”;

c) an up-dated version of “The Whisky Distilleries of Scotland and Ireland”.

There is an important social responsibility component to this project. Alcoholic drinks companies are generally aware of the potential damage which excessive consumption of their products can cause. Many of them participate in industry-wide awareness campaigns or run their own. However, these are aimed mainly at young people and often come across as being either flippant or scare mongering. They are also invariably short-term. I believe a more thoughtful and intelligent approach, with long-term benefits, is to engage the consumer in the story of what is one of the oldest industries or crafts in the world, dating back to the Ancient Egyptians, through knowledge of where the individual whiskies come from (which are often at remote and highly scenic locations), how they are made and, most importantly, by whom. Authenticity, history and lore combine with technical expertise and a certain element of mystique to engage the consumer in such a way that his thirst is quenched not only by the whisky he consumes but by the knowledge he garners in the process. The spin-off for whisky-related tourism speaks for itself.

WN: Thank you for your time. I am looking forward to reading your future books and articles and I hope that the readers might want to revisit your books!